I first met Travis Russell at the factory where he and I were Materials Handlers. “Materials Handlers” is fancy factory-speak for “grunt.”

As Materials Handlers, we were condemned to work in the tumbling and polishing room: a toxic, dungeonous hole, neon-lit and packed with giant industrial tumblers. We worked in the constant roar of the tumblers and the oppressive hum of a massive central vacuum system. Competing with this incredible and constant cacophony was a permeating reek of industrial grease and pulverized aluminium. These elements – combined with no sunlight, long hours and a grueling workload – defined my tenure as a Materials Handler as one of the most dreary, unsavory jobs I have ever worked.

Through all this, my coworker Travis Russell looked happy as pie. I am hard pressed to remember a single time I didn’t look over and see Travis whistling about his work, crisp as a chickadee.

I used to watch how Travis worked. I used to study him carefully. At first I suspected Travis was just an idiot. Maybe he didn’t know better than to be chipper at our grim tasks? But our first conversation – in which I received a tutorial on the anatomy and physics of hummingbirds and we established that Raising Arizona is the best movie ever made – quickly dispelled any suspicion that Travis might have been simple.

If Travis heard me say this, he would probably think it was creepy I’d been watching him so closely. He also might add the correction that he was actually not all that happy as a Materials Handler. I concede to both points. But to the latter, I would maintain that Travis (though he may have been crying on the inside) was, on the outside, a goddamn inspiration. And that is just as good as anything far as I’m concerned.

I would see Travis, buoyant about his work, just happy to see you, and I’d think to myself whatever he’s got, I want some of that.

And so I attached myself to Travis, and that laudable work ethic of his, and I hung on for dear life.

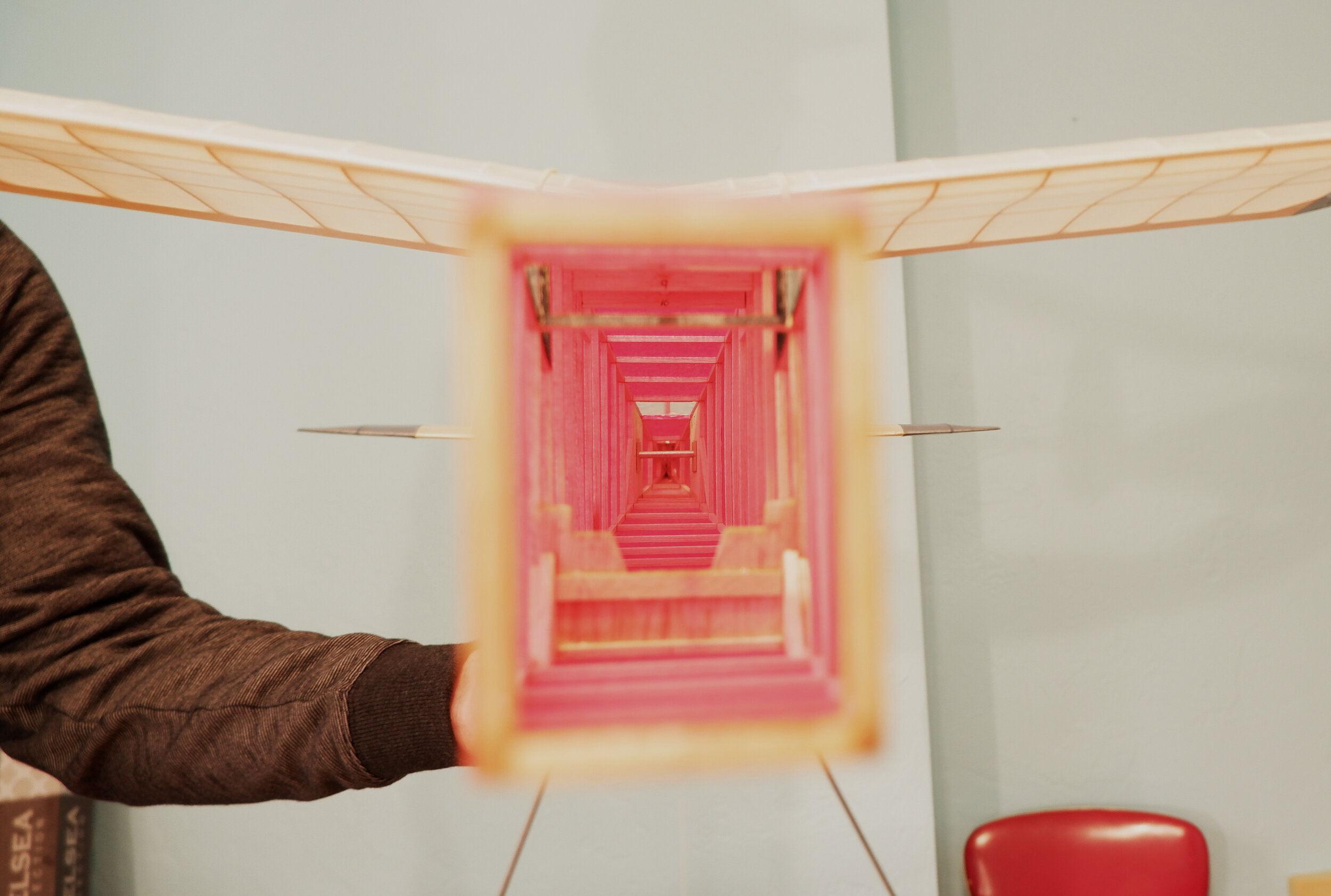

These days, Travis is a teacher in Salem, Oregon. One of his hobbies is building and flying model airplanes. While not nearly as physically and emotionally toxic as our dark days in the tumbling room, building model airplanes is not unlike polishing industrial quantities of metal parts to a mirror shine. Both tasks demand incredible patience and precision and focus in the face an endlessly dreary toil – punishing work which is infrequently interrupted by glimpses of beauty and the fleeting, anonymous victories of solitary work.

Travis loitering at the caboose of the Spruce Goose.

Building model airplanes is a terribly fragile hobby. It seems inevitable that the absurdly delicate planes – thin balsa skeletons bound by tissue paper – are either smashed or crashed or might just fly away. When you consider the time and love put into building just one plane, to see the creation so easily destroyed seems to cartoonishly amplify the crushing disappointments and impermanence of life. I would guess that building model airplanes is good practice in building an existential fortitude to accept how everything we love and create is very temporary.

I gather that Travis’s love of model airplanes and the hobby’s history follows his fascination with and desire to know everything about the physics of flight and propulsion. These are subjects – along with bicycles and bicycle racing, race cars and auto racing, movies and film and so on – of which Travis seems to have gathered an encyclopedic wealth of knowledge.

I never got tired of hearing Travis talk about a thing. One time, we emerged from our day in the tumbling room to find it had dumped snow. Travis offered to put my bike in his trunk and drive me home. The drive, which normally took 15 minutes took us close to two and a half hours and (praise the lord) Travis talked about hummingbirds the whole way. That is a memory that will remain as one of the most special moments in my life and which has, ever since, cursed me with an obnoxious fascination for hummingbirds.

Before I moved from Portland for our new home in Minneapolis, I convinced Travis to show me around his model airplanes and then accompany me to the Evergreen Aviation and Space Museum to continue (on a larger scale) a tutorial on airplanes and flight. Travis was immensely patient of me and my camera, allowing me into his shop to take so many pictures and then later in the museum, standing by while I struggled to get focus on the airplanes and their components.

Like Travis, I have always been fascinated by flight. To see these planes, in all their immensity (Evergreen is home to the Spruce Goose), and complexity is beyond words. The elegance of a propeller, especially those carved from block wood. The something on all helicopters called a God Bolt (or, a Jesus Nut), which Travis explained, is a small pin, just above the main blades that holds the entire works to the main shaft which, if it were to snap (as many have) the occupants of the helicopter would meet God.

Unlike Travis, I can only pass by the details, I appreciate them as one would appreciate a movie. Ask me to explain anything I’d learned and I’d draw a big blank. Whereas Travis seems to hold it all, and have it at the ready. To capture some of the details with a bit more permanence, I sent Travis a couple questions about himself, and flight, and airplanes and he was kind enough to answer them (below).

Q: When did you get into building airplanes?

A: Model aviation started for me on my 11th birthday. My Dad bought me my first Radio Control airplane, which was already built by a club member of my first club. This hobby has been on-again, off-again for 30 years. It’s only been in the last five years that I began building and flying Free Flight models. I built a couple of kits and quickly decided that I preferred building from scratch and plans.

Q: Why airplanes? Why not Dungeons and Dragons figurines or something else?

A: It’s just my personality. I’m much more interested in mechanics and the physical world instead of fantasy. My interest started with birds and progressed to flight and aviation in general. I’m always looking up the stuff. Whether it’s birds, planes or stars and planets. That’s the most interesting thing to me.

Q: What is your favorite design, both model and real-life airplane?

A: This is probably the toughest question. Over a 100 plus years of flight there have been thousands and thousands of model and “real” aircrafts built. Many are interesting or fascinating or just plain beautiful. I love the civilian aircraft of the 1930’s. It’s considered the Golden Age of aviation. Of that era, you can’t go wrong with any choice and I’ve always loved the Beechcraft Staggerwing. Models are just as difficult, but one that always comes up is Claude McCullough’s Charger from 1950.

Q: Can you explain lift so someone like me can understand it?

A: The simplest way to explain lift is; The air on the underside of the wing is moving over the surface of the wing slower than the air moving over the top of the wing. This produces a high pressure area on the bottom of the wing that pushes the wing up. This is achieved with the shape of the airfoil (the tear drop shape that you would see if you sliced the wing like a loaf of bread) and the angle that the wing meets the air. This is known as the Angle of Attack (AoA).

Q: You explained pulse jets of the Buzz Bomb when we were at the museum, for some reason, this stuck with me, can you explain that again?

A: Pulse Jets are simple but complicated, so I will do my best. They are interesting because they can have few to no moving parts, depending on the type. That’s the simple part. How they make power is not too different than how the engine in our cars do. Air and fuel are compressed and then ignited – releasing that energy in a bang. The big difference is that the car engine has pistons that move and up into a combustion chamber where the air and fuel are squished together and then ignited to make the bang that pushes the piston down and sends that energy to the transmission and wheels through a mechanical nightmare. A pulse jet does not have any moving parts so the air and fuel are squished together by geometry. The air is sucked in through a large intake and is then funneled into a much smaller section. This is the combustion chamber of a pulse jet. In this skinny area the air is speeding up and being compressed while the fuel is being injected causing the air and fuel to squish together, just like in our car engine. And just like our car engine, that squished mixture of air and fuel is ignited and it goes bang and that pulse of energy is exhausted through the tailpipe. The energy is turned into forward motion. If you can do this fast enough and enough times it makes for a very fast flying aircraft that makes a loud, droning, buzzing noise due to the fast detonations of the pulse jet. The speed of those detonations is known as the Specific Impulse. Rocket engines for space flight are measured the same way. The higher the specific impulse, the faster they go.

Q: What about building model airplanes do you tend to lose yourself in the most?

A: I think it might be some pursuit of perfection. I’m always striving to do it better, cleaner, lighter and, if possible, faster builds. Faster is really secondary to the others. I’m surrounded by some of the greats, so there is plenty of pride involved. For me it would be embarrassing to show up with something that doesn’t compare. I want them to know that I’m as capable as they are, they just have decades of experience on me. I want to be regarded as a peer and showing up with a well built model is a big part of that. I also enjoy the problem solving, the creativity, the math (teenage me would not believe that one), and designing my own tools. I also love that with some basic tools I can take sheets of balsa that are damn near two dimensional and give them a form. A form that actually flies. Sometimes after building a wing or something, I look over at my stack of balsa and revel in amazement that this wing came from that stack of flat balsa.

Q: Do you have any funny or interesting stories about building airplanes, or flying them with your club?

A: I don’t have any really funny stories, at least not yet. The guys who have been in it for a long time have lots of stories though. I’ll get there. The funniest thing is that they call me “The Kid” and I’m 41 damn years old. My wife asked me the other day if I enjoyed the hobby. It is very hard and at times frustrating and when you’re way behind schedule, it’s definitely stressful. But as Tom Hanks said in “A league of their own”; “The hard is what makes great. If it were easy everyone would do it!”

Q: Any idols you love? Who and why?

A: I don’t have any idols, but I have mentors and people who I admire. One that I admire is George Perryman. George was from my hometown of Griffin, GA and was one of the all time greats. A national champion who built wind tunnel models for Lockheed. He said that the difference between winning and losing was a thermal (column of rising air) and sandpaper. Many of the greats worked at NASA during the heyday. As I mentioned earlier I am surrounded by some of the greats and am fortunate to call them friends and mentors. One of them is Bruce Hannah. He got third place in his first contest when he was 10 years old and that was over 50 years ago. If he has entered an event then everyone else knows they’re probably fighting for second place. He is also one of the best builders around. At first glance of one of his models it’s obvious of how well built it is. I’ll include a few photos of a couple of his models. The orange and black one is a Danish model from 1956 which Bruce drew plans for from a paperback book of plans printed in 1957. The yellow and black one is a model he designed with his dad in the 1960s.

Per Travis: I’m putting a link in for a video called “Adrift on the air.” It’s a period piece, which is one reason I think you might enjoy it. It also does a great job of showing and explaining Free Flight. Also, at any point if you see an old guy with baby blue coveralls and a corncob pipe, that is George Perryman. My hometown hero.